In the sharing economy, you can hire a one-off driver (Uber), courier (Postmates), grocery shopper (Instacart), housekeeper (Homejoy), or just about any other variety of henchman (TaskRabbit). So, what about hiring a hacker?

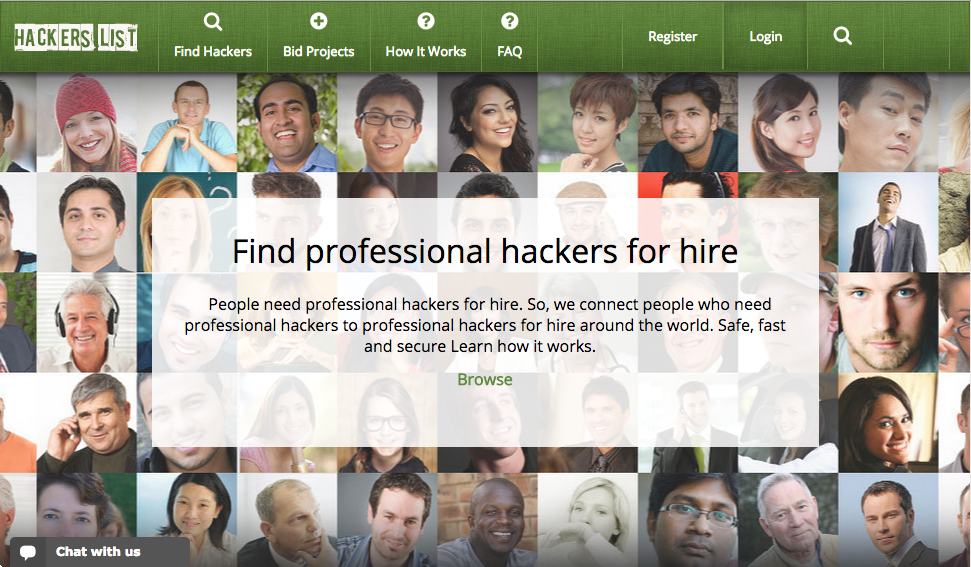

That’s the premise of Hacker’s List, a website launched in November. Anyone can post or bid on a hacking project. Hacker’s List arranges secure communication and payment escrow.

An online black market is, to be sure, nothing new. The rise and fall of the Silk Road received extensive media coverage.

What’s unusual about Hacker’s List is that it, purportedly, isn’t a black market. The website is public, projects and bids are open (albeit pseudonymous), and the owner has identified himself. (He runs a small security firm in Denver.) Hacker’s List was even featured on the front page of the New York Times.

Out of curiosity, I decided to leverage this openness. Who tries to hire a hacker? Is the website as popular as its owner claims? Most importantly, does the website facilitate illegal transactions, or solely white hat hacking?

To answer these questions—and, admittedly, to procrastinate on my dissertation—I cobbled together a crawler. You can find the source on GitHub, and the crawl data on Google Docs.

Here’s the short version: most requests are unsophisticated and unlawful, very few deals are actually struck, and most completed projects appear to be criminal.

… →