Earlier today, the New York Times reported that the National Security Agency has secretly expanded its role in domestic cybersecurity. In short, the NSA believes it has authority to operate a warrantless, signature-based intrusion detection system—on the Internet backbone.1

Owing to the program’s technical and legal intricacies, the Times-ProPublica team sought my explanation of related primary documents.2 I have high confidence in the report’s factual accuracy.3

Since this morning’s coverage is calibrated for a general audience, I’d like to provide some additional detail. I’d also like to explain why, in my view, the news is a game-changer for information sharing legislation.

The Facts

Despite nearly two years of disclosures, the NSA’s domestic Internet surveillance remains shrouded in secrecy. To borrow Donald Rumsfeld’s infamous turn of phrase, it remains one of the greatest known unknowns surrounding the agency.

The following facts are already public.

- The NSA maintains “upstream” interception equipment at many points on the global telecommunications backbone.

- One of the primary legal authorities for domestic upstream surveillance is Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act (FAA).

- The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) has authorized warrantless FAA surveillance in connection with foreign governments, counterterrorism, and counterproliferation. Each of these topics has an associated “certification,” establishing procedures for targeting and minimization.

- The NSA can use FAA upstream Internet surveillance to collect4 traffic that is “to,” “from,” or “about”5 a “selector.” Prior disclosures have emphasized email addresses as FAA upstream Internet selectors.

- In order for a selector to be eligible for FAA surveillance, it must be used by a foreign person or entity outside the United States.

- Intelligence communitya

NSAanalysts can search FAA surveillance data for information involving Americans. Senator Wyden has been a particularly persistent critic of these queries, dubbing them “backdoor searches.”

The primary documents associated with today’s report confirm the following additional facts.6

- The NSA can use FAA upstream Internet surveillance for cybersecurity purposes, so long as there is a nexus with one of the three prior certifications. The most common scenario is where the NSA can attribute a cybersecurity threat to another nation, enabling it to rely on the foreign government certification.

- Internet protocol (IP) addresses and ranges are eligible as FAA upstream surveillance selectors. The Department of Justice approved this practice in July 2012.7

- Cybersecurity threat signatures are also eligible as FAA upstream surveillance selectors. This adds a de facto fourth category of FAA interceptions, since a threat signature cannot reasonably be categorized as “to,” “from,” or “about” a particular address.8 DOJ appears to have approved the practice in May 2012.

- The NSA has acted upon the above legal interpretations. The primary documents make reference to particular FAA cybersecurity operations. Those operations relied on the foreign government certification, and they used IP addresses as selectors.

- Since 2012, if not earlier, the NSA has prioritized obtaining an FAA “cyber threat” certification. From the agency’s perspective, a cyber certification has two desirable properties. First, it would eliminate the nexus requirement. The NSA would be able to intercept traffic associated with a cybersecurity threat, regardless of whether the threat originates with a foreign government. Second, a cyber certification would codify procedures for IP address and signature targeting. The present status of the cyber certification is not apparent; it may have been approved, have been bundled into another certification, still be in progress, or have been set aside.9 It is also not apparent how FAA’s foreignness requirement would be implemented under the certification.10

- When data is exfiltrated in the course of an attack, it often includes sensitive information about Americans. The NSA believes that this exfiltrated data should be considered “incidental” collection, rendering it eligible for backdoor searches. Put differently: when a data breach occurs on American soil, and the NSA intercepts stolen data about Americans, it believes it can use that data for intelligence purposes.

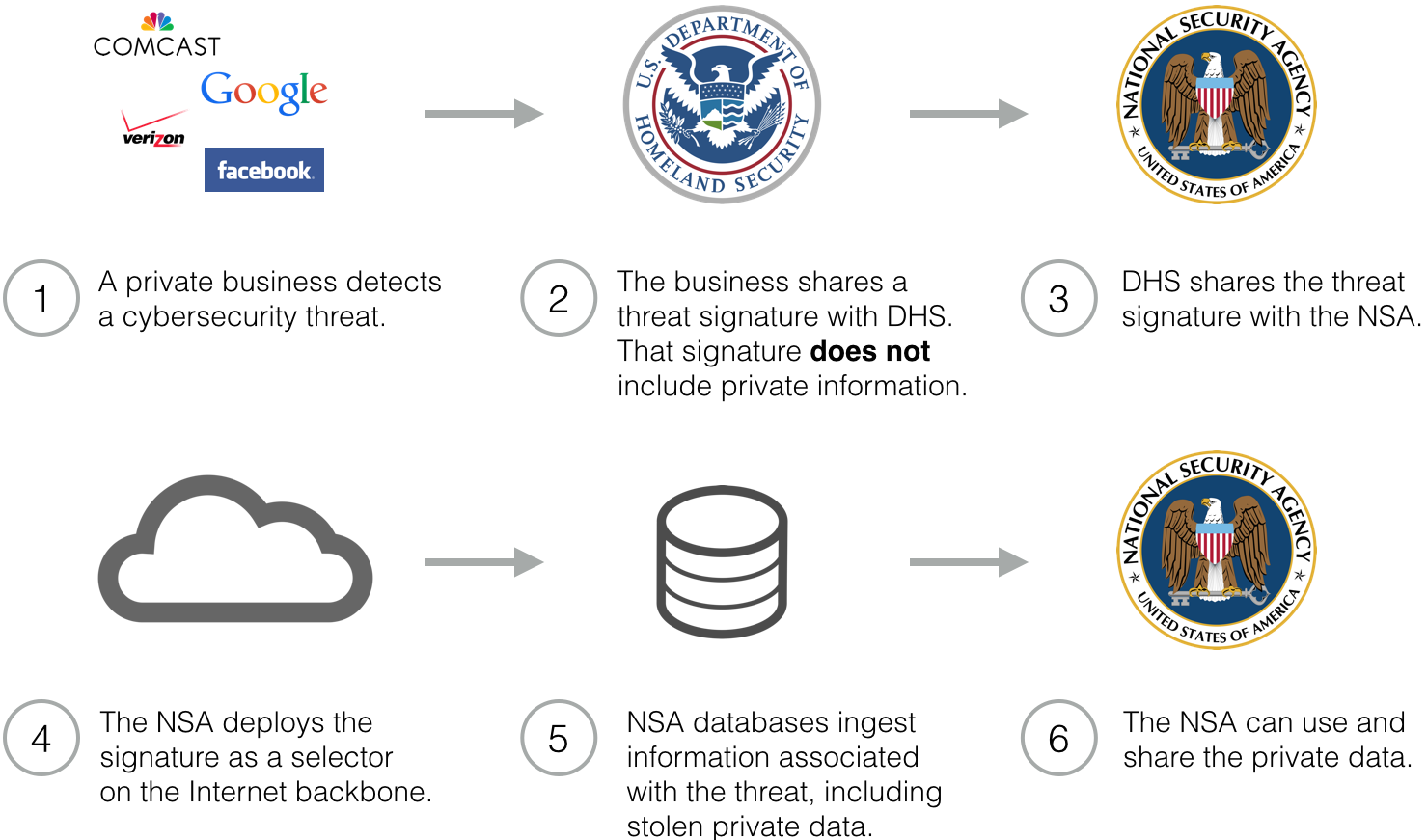

- The NSA collaborates with the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Bureau of Investigation on cybersecurity matters. It receives and shares cybersecurity threat signatures with both agencies. When the NSA wishes to disclose a threat signature to the private sector, it usually routes that information through DHS or the FBI. The NSA is not attributed as the source of the threat signature.

- The FBI does not have its own national security surveillance equipment installed on the domestic Internet backbone. It can borrow the NSA’s equipment, though, by having the NSA execute surveillance on its behalf.

In my view, the key takeaway is this: for over a decade, there has been a public policy debate about what role the NSA should play in domestic cybersecurity. The debate has largely presupposed that the NSA’s domestic authority is narrowly circumscribed, and that DHS and DOJ play a far greater role. Today, we learn that assumption is incorrect. The NSA already asserts broad domestic cybersecurity powers. Recognizing the scope of the NSA’s authority is particularly critical for pending legislation.

Information Sharing

In recent years, domestic cybersecurity legislation has focused on information sharing. The notion is that private businesses are not swapping vital threat information, owing to potential legal liability. (Like the overwhelming majority of computer security professionals, I believe that premise is inaccurate.)

There are at least five different information sharing bills presently before Congress. CISPA passed the House in 2012; it was widely condemned by an online grassroots effort, and it ultimately drew a veto threat from the White House. This year, both PCNA and NCPAA have cleared the House, and the Senate is likely to take up information sharing soon.

The conventional privacy criticism of information sharing legislation goes, roughly, like this. Private online activity is protected by a longstanding legal framework, including the Wiretap Act and the Stored Communications Act. Information sharing legislation would drill gaping, ill-defined holes in those safeguards. Businesses would increasingly share highly sensitive information with the government, which could in turn use and share that information for law enforcement and other purposes.11 In Senator Wyden’s memorable phrasing, information sharing legislation is “a surveillance bill by any other name.”

The consistent response to this line of criticism has been to emphasize that information sharing legislation is not a grant of surveillance authority. When PCNA was under consideration, for instance, Representative Schiff insisted: “[L]est anyone be confused, this bill makes clear in black and white legislative text that nothing authorizes government surveillance in this act. Nothing.”

That perspective is only half true. PCNA does explicitly decline to grant new cybersecurity surveillance powers, and NCPAA has a roughly parallel provision.

But the NSA already has sweeping cybersecurity surveillance authority. It doesn’t need a new statutory grant of power. By feeding threat signatures to the NSA, information sharing would activate the agency’s existing authority.

This understanding of the NSA’s domestic cybersecurity authority leads to, in my view, a more persuasive set of privacy objections. Information sharing legislation would create a concerning surveillance dividend for the agency.

Because this flow of information is indirect, it prevents businesses from acting as privacy gatekeepers. Even if firms carefully screen personal information out of their threat reports, the NSA can nevertheless intercept that information on the Internet backbone.

Furthermore, this flow of information greatly magnifies the scale of privacy impact associated with information sharing. Here’s an entirely realistic scenario: imagine that a business detects a handful of bots on its network. The business reports a signature to DHS, who hands it off to the NSA. The NSA, in turn, scans backbone traffic using that signature; it collects exfiltrated data from tens of thousands of bots. The agency can then use and share that data.12 What began as a tiny report is magnified to Internet scale.

Sometimes I write shorter stuff at @jonathanmayer.

This was a personal project; it did not make use of Stanford University resources.

1. While I’m not a fan of the “cyber” prefix, I believe it is important to this particular piece. Apologies.

Also, I focus here on “upstream” surveillance of Internet traffic. Many of the same observations apply to stored data, under the PRISM program.

2. Accepting was, candidly, a very difficult decision. I have mixed views on large-scale government leaks, and I appreciate the legitimacy and importance of keeping intelligence operations classified. I participated in this project because it centers on secret interpretations of United States law, and because it is highly relevant to ongoing legislative and policy debates.

I recognize that friends and colleagues in the intelligence community may disagree with my decision to participate in this project. I greatly value those relationships, and I sincerely hope that my participation will not impair them. I would also emphasize that both the Times report and this blog post deliberately omit specific surveillance targets, resulting intelligence, and agency personnel.

3. Early coverage of NSA programs was, unfortunately, riddled with legal and technical misunderstandings. Computer security and privacy journalism is markedly better when it incorporates advance review by lawyers and computer scientists with relevant expertise.

4. The scope of what information the NSA temporarily buffers remains deeply ambiguous. Some observers believe that the agency temporarily retains (but does not “collect,” within the legal meaning) all one-end foreign Internet traffic.

5. The technical implementation of “about” collection appears to involve matching strings in traffic flows, plus filtering for at least one IP address outside the United States.

6. Since the Snowden archive ends in mid-2013, some of these facts may be outdated.

7. It is not apparent whether this was the first instance of IP address selectors, or IP address selectors specifically for cybersecurity. It is also not apparent whether the NSA sought the FISC’s advance permission for using IP address or signature selectors.

Prior reports had suggested IP-based targeting was allowed, and it was widely assumed to be permissible among surveillance scholars. It certainly comes as little surprise.

8. In precise surveillance law lingo, signature selectors are not “to,” “from,” or “about” a specific “communications facility.”

9. After reviewing recent public statements by a number of intelligence officials, I do not believe there is particularly strong evidence for or against the existence of a cyber certificate.

10. Even modestly sophisticated intrusions are, at least at first, difficult to attribute. In the absence of further information, the NSA would presumably assume foreignness. And even if the agency implemented a technical foreignness requirement (e.g. a one-end foreign IP filter), many run-of-the-mill attacks are either based outside the United States or bounce through a proxy outside the United States.

11. Subject to the usual Section 702 minimization procedures.

12. Again, subject to minimization procedures.

a. Thanks to Charlie Savage for suggesting a clarification. The statement was literally true—NSA analysts can conduct backdoor searches under FAA. Since this piece is focused on upstream surveillance, and since the rules for backdoor searches are nuanced and ambiguous, here’s some further detail.

Present NSA policy appears to voluntarily limit U.S. person backdoor queries to stored communications (PRISM). FBI and CIA analysts can also conduct U.S. person backdoor queries on PRISM data, and may be able to request backdoor queries on FAA upstream data; public disclosures are ambiguous on the issue.

(Aside 1: while these are the rules for U.S. person backdoor queries, they are not always followed. According to the NSA’s reports to the President’s Intelligence Oversight Board, for instance, noncompliant queries do occur.)

(Aside 2: this post is focused on the FISA Amendments Act. There are other legal structures for cybersecurity surveillance, including FISA Title I and Executive Order 12333. The backdoor query rules for those upstream and cloud service collections may differ.)

This much is certain about FAA cybersecurity surveillance: If the NSA snoops on hackers as they move stolen data over the Internet backbone, agency analysts can sift through that information—other than with explicit U.S. person queries. If the NSA, FBI, or CIA snoops on hackers as they move stolen data through a cloud service, such as Dropbox or Gmail, analysts can sift through that information—including with explicit U.S. person queries.