In the sharing economy, you can hire a one-off driver (Uber), courier (Postmates), grocery shopper (Instacart), housekeeper (Homejoy), or just about any other variety of henchman (TaskRabbit). So, what about hiring a hacker?

That’s the premise of Hacker’s List, a website launched in November. Anyone can post or bid on a hacking project. Hacker’s List arranges secure communication and payment escrow.

An online black market is, to be sure, nothing new. The rise and fall of the Silk Road received extensive media coverage.

What’s unusual about Hacker’s List is that it, purportedly, isn’t a black market. The website is public, projects and bids are open (albeit pseudonymous), and the owner has identified himself. (He runs a small security firm in Denver.) Hacker’s List was even featured on the front page of the New York Times.

Out of curiosity, I decided to leverage this openness. Who tries to hire a hacker? Is the website as popular as its owner claims? Most importantly, does the website facilitate illegal transactions, or solely white hat hacking?

To answer these questions—and, admittedly, to procrastinate on my dissertation—I cobbled together a crawler. You can find the source on GitHub, and the crawl data on Google Docs.

Here’s the short version: most requests are unsophisticated and unlawful, very few deals are actually struck, and most completed projects appear to be criminal.

Who Tries to Hire a Hacker?

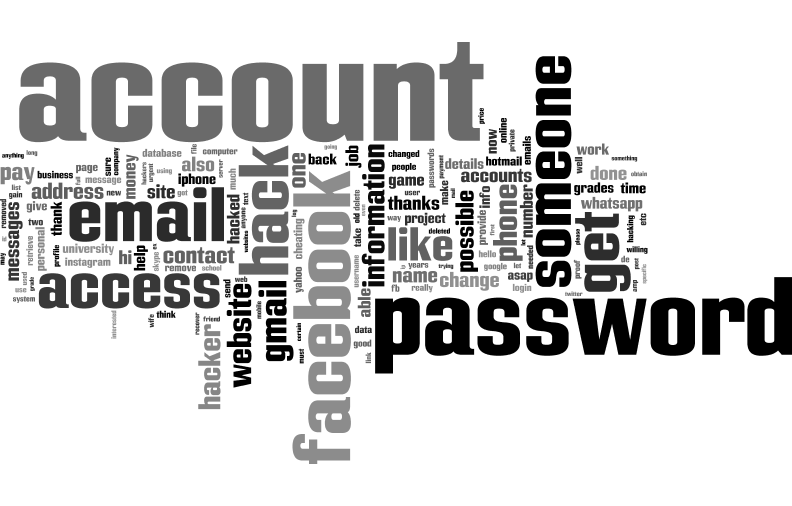

A majority of requests1 involve compromising cloud service accounts. The most common targets are Facebook (expressly referenced in 23% of projects) and Google (14%). Motives vary, and often involve a business dispute or jilted romance. (How cliché.)

The second most common scenario (8%) arises from academia. There is, apparently, enormous demand for artificially improving grades — especially at the undergraduate level. Targets include the University of California, UConn, and the City College of New York.

A final fact pattern that bears mention is altering search results. About 3% of projects involve burying some embarrassing tidbit, essentially an ersatz Right to be Forgotten.

These observations come with an important caveat: the requests on Hacker’s List are overwhelmingly cheap and unsophisticated. The median project is priced from $200 to $300, and many descriptions reflect technical misunderstanding. Hacker’s List certainly isn’t representative of the market for high-end, bespoke attacks. But the site does seem a fair cross-section of the hacks that ordinary Internet users might seek out.

As an aside, many users on Hacker’s List are trivially identifiable. Some submissions explicitly include a name, contact information, or a street address. Also, owing to the design of the site’s social integration, I was able to match 25% of active accounts to a Facebook profile. So much for “discreetly” hiring a hacker.

How Popular Is Hacker’s List?

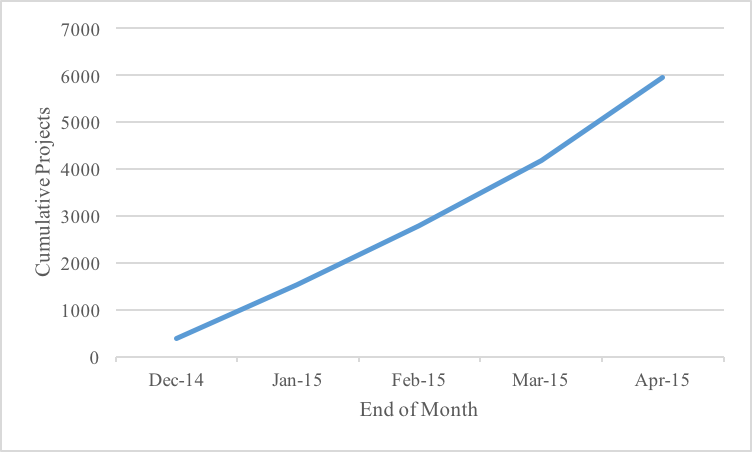

The owner of Hacker’s List has claimed that the site “exploded” and “went viral.” Visitor traffic certainly shot up following January press coverage.

Actual usage of the site, though, has been lackluster. There are only about two to three projects posted per hour, and month to month growth is slim. By any usual startup benchmark, Hacker’s List is hardly a sensation.2

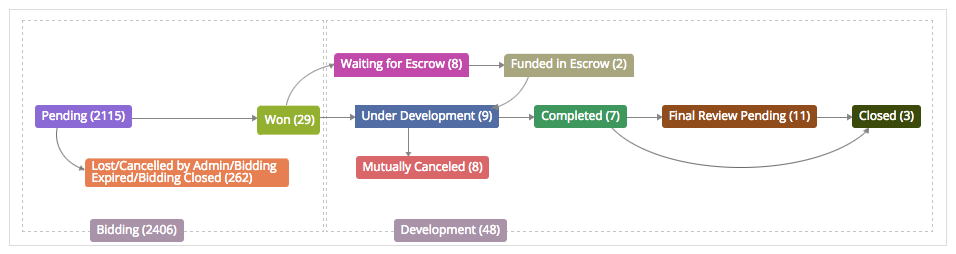

What’s more, the overwhelming majority of hacking requests go nowhere. Fewer than 0.1% of projects advance to an actual hack.3

The owner of Hacker’s List told the New York Times last week that over 250 jobs have been completed. That claim is not consistent with the site’s own data, which includes just 21 finished tasks.

Money does appear to change hands on Hacker’s List, to be clear. It’s just… not for hacking. Rather, you have to pay the site $3 to bid on a project. And each time you fund your account, there’s a minimum of $10.

Are Completed Projects Legal?

Hacker’s List “is intended for legal and ethical use.” And, according to the owner, “[n]o one is going to complete an illegal project through my website.”

How about “i need hack account facebook of my girlfriend,” completed for $90 in January? Or “need access to a g mail account,” finished for $350 in February? Or “I need [a database hacked] because I need it for doxing,” done for $350 last month?

This much is certain: the overwhelming majority of posts solicit criminal activity, and most of the (few) completed projects appear to be crimes.

Is a Hacker Marketplace Legal?

I’d like to close by taking a step back. Is the very concept of a hacker marketplace compatible with American law?

Websites are, for the most part, not liable for user misdeeds. For nearly two decades, federal law has expressly immunized online services.

A hacker marketplace doesn’t benefit from this immunity, though. There’s an explicit exception for federal criminal offenses. That includes violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the federal hacking law.

So, is the operator of a hacker marketplace a criminal? Liability as an accomplice or conspirator is certainly possible. The operator of the Silk Road, for instance, was convicted on a hacking conspiracy charge (among others).

Whether a website owner would be culpable is an exceedingly fact-specific issue. The precise legal question is: did the owner actually intend that crimes be committed, or did they merely know that crimes would be committed?4

That’s a very subtle distinction to base a business on. Especially when the potential downside involves years in federal prison.

At best, then, a hacker marketplace exists in a legal limbo.

I write shorter stuff at @jonathanmayer.

1. The results that I report are based on projects and bids that my crawler could access. There appear to be a number of Hacker’s List project IDs that are not associated with a live project page. What happened to those projects, I cannot say. I was able to recover some details via the Hacker’s List revision tracker; as with the live projects, almost all are unlawful.

2. The following figure is based on the last revision date associated with each project. It includes all projects in the revision tracker, many of which do not have a live project page.

3. The data in the following figure is drawn from the Hacker’s List bidding interface, which allows querying for bids by stage of the bidding process. The figure is adapted from the Hacker’s List control panel.

4. If you’d like to learn more about that (hazy) distinction, I recommend the classic case of People v. Lauria.